- Daniel Casarin: A tuo avviso come dovrebbe essere letta e ‘digerita’ la storia dell’architettura dagli architetti contemporanei?

- Daniel Casarin: In your view how should historical architecture be read and ‘digested’ by contemporary architects?

Peter Macapia: Questa è una domanda interessante. Se intendi esempi passati storici o stili d’architettura e se la intendi anche in relazione alle problematiche critiche contemporanee, sicuramente, ma è relativo, la domanda veramente importante è “come possiamo utilizzare le architetture storiche?”. Per esempio uno dei miei progetti preferiti è la sala del Mercato Traiano di Apollodoro di Damasco (sapevi che Traiano lo fece uccidere? Che sbaglio!), in quel caso si cercava risolvere le problematiche della densità urbana, della luce e dello spazio creando un’infrastruttura ibrida.

Questo progetto vedo questo in relazione ad un fenomeno molto importante a Tokyo, è incredibile perché il progetto mostra una relazione contro una forma, una sorta di nodo, uno scambio di energia e tensione. Ciò ci dice, che la densità e la pressione viene trattata non tramite la metrica ma tramite modelli alternativi come la topologia. Questo fatto poi lo possiamo paragonare alla “città di domani” di Le Corbusier e considerare le implicazioni di un senso della geometria e del controllo iper-razionale quasi paranoico. Ho scritto un saggio su questo argomento: “Dirty Geometry for Log comparing it to Tati’s Playtime” che solleva un’altra questione: l’architettura esiste nei film tanto quanto nell’edilizia, il film gioca anche con problematiche di organizzazione. L’unico problema nel utilizzare esempi del passato nella mia opinione è quando questi sono coordinati per giustificare un progetto – e questo è un pensiero iconico o simbolico che nega l’opportunità di progettazione per essere rilevante oggi.

Peter Macapia: This is an interesting question. If you mean by historical past examples or styles of architecture and if you also mean in relation to contemporary critical issues, then of course. But it is relative. The question is really how do we use those examples. For instance of my favorite projects is Trajan’s market Hall by apolodorus of damascus (did you know Trajan had him executed? What a mistake) which addresses issues of urban density, hybrid infrastructure and architecture, structure, light and space. I see this in relation to very important phenomena in Tokyo. Its amazing because it is so very antiform – its a kind of knot, an exchange of energy and tension.

It says, deal with density and pressure not through metrics but through alternative models like topology. Then we can compare it to, say Le Corbusier’s city of tomorrow and consider the implications of a hyper rational even paranoid sense of geometry and control. I wrote an essay about this called Dirty Geometry for Log comparing it to Tati’s Playtime which raises another point: architecture exists in film as much as it does in buildings. Film also plays with problems of organization. The only problem with using past examples of design in my opinion is when they are marshalled to justify a design – that’s iconic and symbolic thinking which denies design the opportunity to be relevant for today.

- Daniel Casarin: La città e i suoi palazzi, i suoi spazi verdi, i centri storici e le periferie, potrebbero essere concepiti come un vero organismo dinamico; qual è la tua concezione del macrocosmo come città e microcosmo come singolo edificio?

- Daniel Casarin: The city with its buildings and its green spaces, historical centers and periphery could be conceived as a true “dynamic organism”, what is your conception of macrocosm as city and microcosm as single building?

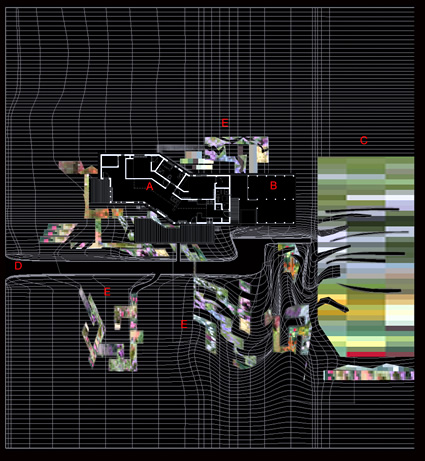

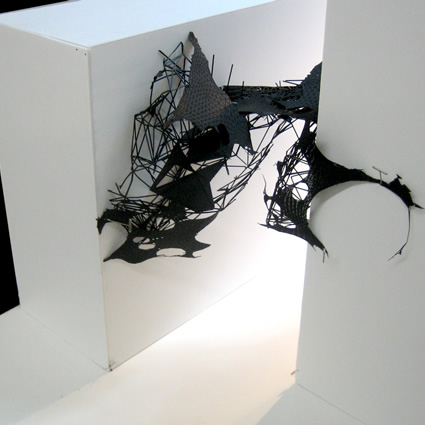

Peter Macapia: In scala locale il palazzo è un artefice geometrico che mantiene un rapporto continuo fra le parti. Le qualità relazionali di questi rapporti però non sono metrici ma topologici. Questo è un tipo di totalità, l’altro riguarda la città, ma non è più così complessa topologicamente come pensiamo, credo che gli architetti spesso sbagliano su questo punto. Entrambi sono reti e l’opportunità d’inventare uno in relazione all’altro è cruciale e vale in tutte due le direzioni: un architetto dovrebbe vedere il suo progetto come una reinvenzione della città e questo fondamentale. I padiglioni di “Geometria Sporca” sono un esperimento di questo lavoro. Sono fatti per abitare la città come veramente diversi tipi di mostri di un film. Alcuni molto docili ed innocenti altri più minacciosi.

Ognuno cerca di creare un nuovo senso di spazio pubblico come se l’osservatore l’avesse appena scoperto. Non sono piazze né altri ovvi trucchi urbani, sono più tenui ed elusivi, e sono creati per essere sperimentati come una sorta di “sabotaggio” che ti aspetta appena giri l’angolo. Lo spazio pubblico è la vera domanda importante. Perché il palazzo dovrebbe avere un determinato effetto una volta che lo incontri, facendoti desiderare una città diversa, una città più appassionata e più intensa. Credo che ho imparato questo fatto e queste relazioni soprattutto da Bernard Tschumi, quando un giorno mi confidò che lui non progetta mai un palazzo ma piuttosto una strategia. Credo che questo metodo sia davvero brillante e che sia il tipo di atteggiamento giusto per portare l’architettura e il design ad un alto livello.

Peter Macapia: At a local scale a building is a geometrical artifact that makes continuous relation between its parts. The relational qualities of those relations however are not metric but rather topological. That’s one kind of totality. The other is the city, but it’s no more topologically complex. I think that’s a mistake architects often make. They are both networks and the opportunity to reinvent one in terms of the other is crucial. It goes both ways: an architect should see his or her project as reinventing the city. The Dirty Geometry pavilions are an experiment in this. They are meant to inhabit the city as different kinds of B Movie monsters really. Some very docile and innocent and others more menacing.

Each one tries to create a new sense of public space as though the viewer just discovered it. They aren’t piazzas and other obvious kinds of urban tricks. They are more subtle and elusive, they are meant to be experienced as a kind of sabotage waiting around the corner. Public space is the real question here because a building should have the effect that once you encounter it, it makes your desire for the city different, more passionate, more intense. I think I learned this most from Bernard Tschumi who once told me that he never designs a building but rather a strategy. I think that’s brilliant and that is the kind of attitude that makes architecture and design relevant.

- Daniel Casarin: A tuo avviso quale tipo di dinamica sociale può promuovere un’architettura organica?

- Daniel Casarin: In your view what kind of social dynamics does organic architecture encourage?

Peter Macapia: Questa è la parte più impegnativa. Prima di tutto, io non credo nell’ingegneria sociale e non credo che sia il lavoro di un architetto quello di dire alle persone come essere. Ma piuttosto dare a loro qualcosa su cui pensare. Secondo, ciò che è possibile considerare come “dinamiche sociali” deve essere chiarito, quindi lasciami suggerire ciò che significa. Una dinamica sociale è una valutazione continua di se stessi e il modo in cui ci relazioniamo con gli altri non direttamente ma tramite diversi medium, inclusa l’architettura. A questo punto ricorre spesso questa domanda: “a che punto ho dato per scontata la mia posizione nel sistema?” Perché se hai smesso di farti domande significa che ti sei dimenticato dove sei e ti stai muovendo alla cieca effettivamente, e che non sai dove sia il resto “dell’oceano” né dove si trova la spiaggia e quindi se vuoi uscirne dalla nave in cui navighi sei nei guai.

Il tipo di architettura e design al quale aspiro è quello che ti lascia ad interrogarti sul Sistema non soltanto ad accettarlo. Certo, vorrei che i miei progetti ti facesse vedere le cose in maniera diversa, magari nuova, ma questi miei lavori vogliono essere soltanto l’inizio. La prima casa che ho progettato aveva lasciato i clienti senza fiato per il modo in cui ho progettato lo spazio, la struttura e la luce. Ma sai che cosa è successo? Per un anno intero mi hanno chiamato ogni 2, 3 giorno per raccontarmi come le luci e lo spazio stessero cambiando non solo durante l’arco della giornata ma di giorno in giorno e questo fatto non l’avrei potuto anticipare. Il sistema architettonico non smette di crescere una volta che è costruito, dovresti puntare sul fatto che le persone sperimentino ciò che hai creato come completamente nuova, ogni qual volta si impegnano con essa. Creando un rapporto biunivoco. Se questo po’ essere definito organico, cosi sia, l’abbraccio completamente. E’ proprio questa la magia della progettazione e dell’architettura, dovrebbe avere una sua vita propria.

Peter Macapia:This is the toughest part. First, I don’t believe in social engineering. I don’t think an architect’s job is to tell people how to be but rather offer them something to think about. Second, social dynamics needs to be clarified so let me suggest what I think it means; it means continual self evaluation of how we relate to one another not directly but through various media, including architecture. It is always this question: at what point have I just assumed my agency in the system? Because if you’ve stopped asking questions it means you’ve forgotten where you are and you are in fact moving blindly. You have no idea which way lies the rest of the ocean and which way lies the shore and so if you want to get out of the ship you’re in, you’re kind of screwed.

The kind of architecture and design I aspire to is that which leaves you interrogating the system, not merely accepting it. Sure I want it to make you see things in a different and new way, but that is just the beginning. The first house I designed left the clients breathless with the way I designed the space, the structure and the light. But you know what? For an entire year they called me every few days telling me how the light and the space were changing not only on a daily basis, but from day to day. I couldn’t have anticipated that. The architectural system doesn’t stop growing once it’s built. You should want people to experience the thing you make as entirely new each time they engage it. And if that’s organic, so be it, I completely embrace it. But that’s the magic of design; it should have a life of its own.

- Daniel Casarin: Parti sempre da una prima analisi di forme tramite programmi come il CFD e l’FEM, cosa puoi estrapolare da questo metodo di lavoro e quali soluzioni innovative hai raggiunto? Come possono queste scoperte informare o evolvere in un’architettura sostenibile e organica?

- Daniel Casarin: From your studies and analysis on CFD and FEM upon arriving at an ideal first pit stop in you work, what are you able to extrapolate from this method and what innovative solutions have you reached? How can these findings inform or evolve sustainable and organic architecture?

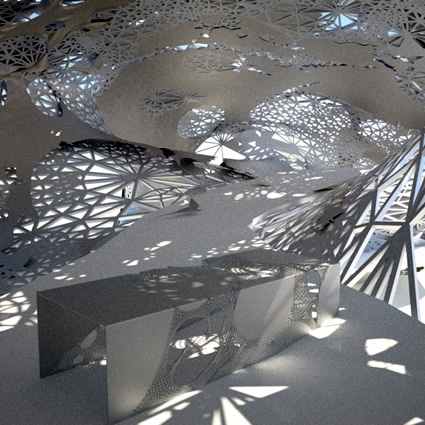

Peter Macapia: Questa è una bella domanda e la risposta potrà stupirti! Trova un modo per abusare di ogni strumento che ti è dato e scoprirai qualcosa di molto ricco. Certo utilizzo il CFD e l’FEM per analizzare alcune questioni ma quello difficilmente è innovazione nella progettazione, ma soltanto suggerisce un’ottimizzazione che rappresenta soltanto un concetto furbo. Posso ottimizzare un palazzo, ma allora? Questo non necessariamente cambia il modo in cui reinvento l’esperienza di uno spazio, lo può fare sì, ma non è inerente; alla fine devo prendere una decisione e quello che scopro quando utilizzo questi strumenti è che loro introducono modelli di organizzazione che posso spostare da un dominio ad un altro, diciamo dal movimento delle masse termiche al flusso delle forze strutturali.

Il filosofo Wittgenstein ha fatto questo punto sulla matematica: l’invenzione e la trasformazione dei segni conformi ad un nuovo paradigma. Il trucco è che questo non succede a livello concettuale ma come un effetto della costante esplorazione delle tecniche, quindi quei programmi come il CFD e l’FEM sono significativi nella misura in cui riguardano le mie tecniche e il comportamento di quei fattori che fanno parte di ciò che chiamiamo semplicemente architettura. Assolutamente durante il progetto devo sedermi accanto ad un altro ingegnere per assicurarmi che tutto quanto il mio progetto stia in piedi, che non crolli, ecc. ma questo è soltanto chiedersi se stai utilizzando la colla giusta o meno.

Il traguardo del design è quello di tastare in qualche modo tramite le tue tecniche, possibilità e limiti. Non è un’interpretazione virtuosa, ma è il senso innato di ciò che hai realizzato, ossia che il tuo progetto ha una vita propria e che devi riuscire a costruirlo e lasciarlo poi andare per poi osservare che così facendo, ciò va oltre le tue intenzioni. Cosi è come io vedo e immagino il design come inseparabile dall’arte. Sto lavorando su una serie di sedie che utilizzano le dinamiche dei fluidi e quello che ho trovato e scoperto è che la geometria che produco è molto efficace per il comportamento topologico dei fluidi, le sedie hanno una complessità incredibile che le fa sembrare leggere e delicate, ma non lasciarti ingannare, perché potrebbero sostenere un elefante. Questo si realizza perché sono una sola superficie continua.

Ma per arrivare a questo devo continuamente intervenire nel comportamento dei fluidi e della struttura geometrica da cui deriva. E’ un processo costante da mettere a punto finché la cosa crea un’armonia propria (o disarmonia se è quello che stai cercando). Mi piace molto questo processo. Un giorno feci una conferenza al Malaquais a Parigi e dopo aver mostrato molti progetti utilizzando il CFD e l’FEM un professore della scuola ne fu molto disturbato, il mio francese non è molto buono ma dopo aver sentito la sua critica per due minuti l’ho interrotto e gli ho chiesto: “Mi stai chiedendo se credo che il design sia soltanto una questione di schiacciare un pulsante sulla tastiera e di far partire una simulazione al computer?” E lui ha risposto con un grosso sorriso, Sì. E io ho detto, No. E il suo sorriso diventò ancora più grande e si sedette.

Adesso sto curando una mostra che si chiamerà Natalgenesis che punta al significato di testimoniare la nascita di qualcosa mentre nasce, ma significa anche il fatto di intervenire costantemente durante il processo, ed è lì dove vedo l’importanza della sostenibilità e l’informatica oggi. Si sperimenta costantemente con lo stato di qualcosa che diviene. Sai come Michelangelo tagliava il suo marmo? Ci versava dell’acqua sopra per vedere dove fluiva in relazione al granulosità e porosità della superficie, questa tecnica era veramente cosi rilevante per il modo in cui lui la scolpiva. E sono abbastanza sicuro che non egli l’ha fatto una sola volta all’inizio ma ogni qualvolta per andare più in profondità nel marmo. Questo è lo splendore del Rinascimento e credo che questo sia il motivo per cui la sua ultima Pietà sia molto più formidabile della prima.

Peter Macapia: This is a good question and the answer might surprise you; find a way to abuse every tool you’re given and you’ll discover something really rich. Sure I use CFD and FEM to analyze things. But that’s hardly innovation in design. It only suggests optimization which is a tricky concept. I can fully optimize a building. But so what? It doesn’t necessarily change the way I can reinvent the way someone experiences a building. It can but doesn’t inherently. In the end, I have to make a decision. And what I discover when I use these tools is that they introduce patterns of organization that I can move from one domain, say, the movement of thermal masses to the flow of structural forces. The philosopher Wittgenstein made this point about mathematics: invention is the transformation of signs according to a new paradigm. The trick is that this doesn’t occur on a conceptual level but rather as an effect of the constant exploration of techniques.

So those programs only are meaningful to the extent that they raise question about my techniques and the behavior of those things that are the parts of what we call architecture. Absolutely at some point I have to sit down with another engineer and make sure the thing doesn’t fall apart, or collapse, or whatever. But that’s really just asking whether or not you are using the right kind of glue. Everything behaves in some way or another and the goal of design is to kind of feel this through your techniques. Its not virtuosity of performance. Its the innate sense that what you make has to have a life of its own. And you have to both set that up and walk away from it and let it do what it is supposed to do but in a way that goes far beyond your intentions. That’s how I see design as inseparable from art. I’ve been working on a series of chairs using fluid dynamics, and what I found is that the geometry that I produce is super efficient because of the topological behavior of fluids. The chairs have this incredible intricacy that makes them look light and delicate and fragile. But don’t be fooled. They could support an elephant.

That’s because the thing is really one entire continuous surface. But in order to get there I have to continually intervene in the behavior of the fluid and geometrical scaffolding from which it behaves. It’s a constant process of fine tuning until the thing has harmony (or discord if that’s what you’re after). I like this process a lot. In a lecture I gave at Malaquais in Paris after showing a lot of work using CFD and FEM a professor from the school got really upset. My French is not so good, but after about two minutes of listening to his diatribe I interrupted him and asked: Are you asking if I think design is just a matter of pushing a button on the keyboard and running a simulation? And he said with a big smile, Oui. And I said, Non. And his smile got even bigger and he sat down.

Right now I’m curating a show called natalgenesis - it means witnessing the birth of something as it is being born. But it also means constantly intervening in the process. That’s where I see the importance of things like sustainability and computation today. You constantly experiment with the state of something’s becoming. Do you know how Michelangelo cut his marble? He would pour water over it to see where it flowed in relation to its grain and porosity. That’s a technique as relevant as the way in which he chisels it. Because I’m quite sure that he didn’t have to do that once, but every time he got deeper and deeper into the marble. And that’s the brilliance of the Renaissance right there. I think that’s the reason why his last Pieta is more powerful than his first one.

[ Links utili e approfondimenti ]

Nessun commento

Attualmente non ci sono commenti per Architettura della Vita e Architettura Vivente. [ PT. 2 ] Peter Macapia Oltre le Forme e lo Spazio: Viaggio nell’Architettura, nella Matematica e nella Fisica fra Natura e Artifico passando fra Vitruvio e Wittgenstein. Perchè non ne aggiungi uno?